Winder, Idaho Historical Artifacts

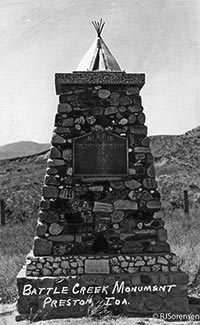

The thin density and the types of artifacts found in Winder, Idaho confirm an absence of continuous aboriginal occupation. The best formed and preserved artifacts occurred at the site of the Battle of Bear River near the mouth of Battle Creek. From 1879, early settlers reported finding numerous human and animal bones, grinding instruments, projectile points and digging tools along the creek, near the river, in crevices, in ravines, in swamps and on the open ground surfaces. Many of the remains were turned up by plowing and other cultivation. Local residents associated these finds with the victims of the battle, but an undetermined number probably originated from earlier deposits. Farmers kept the articles that they found interesting in piles along fence lines or in barnyards until 1932 when the Daughters of the Pioneers collected rock and artifact specimens to build into a monument commemorating the battle.

The monument exhibits an assortment of nicely-formed stone artifacts of various colors, compositions, shapes and sizes: manos, pestles, flat milling slabs, fleshers, scrapers, and one large white metete with a deep basin, a type of milling implement usually identified with the corn cultures (Fremont Culture) of central and southern Utah, but rarely found in northern Cache Valley.

Regrettably, many of the artifacts in the monument are not of local origin. The monument committee solicited interesting rocks from any location. Each was to be accompanied by a legend of the effort made in securing it, of the place from which it came, of historical significance,

or what not. One rock came from as far away as the mines in Alaska. The primary purpose in collecting the stones was to represent families, clubs, societies, organizations, or communities in the monument.

The rocks are not identified at the site of the monument, but the are on file at the Daughters of the Pioneers office in Preston, Idaho. Removal from their original location depreciates the value of those which are native to Winder, and drainage, leveling, cultivation, road construction, and railroad building in the places where the local artifacts were found hampers evaluation.

A less disturbed archaeological site is located farther north along Battle Creek in the vicinity of a spring in section 19, township 14. This site consists of an open hillside and both sides of the Battle Creek gorge for approximately one-half of a mile southward. The artifact distribution is thin compared to that reported at Battle Creek and the implements are more crudely fashioned.

Private collections in Winder exhibit broken or whole milling slabs, most of which were taken from this site. The most common are of medium-grained natural abrasives, usually sandstone. They are almost flat and rarely over six centimeters thick, with a shallow milling area worn to a smooth polish with use. They vary in size from thirty-eight to forty-eight centimeters long and from twenty-four to thirty-one centimeters wide. Ordinarily oval or rectangular, they are not always carefully shaped or finished around the edges. One end is sometimes pitted to provide a small cradle for cracking seeds. As far as could be determined, the stone from which they were formed is not indigenous to Winder. It is of finer grain and lighter in color than native sandstones.

Manos are of the same materials, loaf-shaped, and of a size to fit comfortably into a small woman's hand (about 13-16 cm. long). No mortars and pestles are reported to have been found at this site. On a dry, windy hillside about one-half of a mile above the creek, a thin distribution of obsidian chips and points was observed.

This is in a never cultivated area of sagebrush, native grasses and cactus which is assiduously guarded by rattlesnakes and mosquitoes. Although the area is seldom visited, residents of Winder reported finding larger and more intricately formed flint and other stone points there in the past. These were less commonly found and more highly treasured by collectors than the obsidian points. The removal of larger arrowheads from the site obscures an accurate picture of the area.

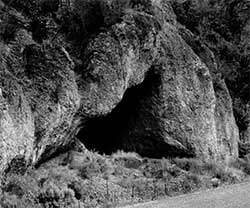

At this site the gorge is a wild tangle of brush, sinkholes, quicksand and landslides. Before irrigation of the nearby farmlands caused extensive erosion, a series of at least four small caves, located on the east bank and several on the west side of the gorge, contained evidence of Indian occupation, Difficult to reach because of loose clay on the inclines below them and sinkholes above, these caves were seldom explored.

Once reached, they were barely high enough to permit a child ten years of age to stand upright. The rear recesses were smoke-blackened, seepage was evident in some, and frequent small ceiling cave-ins covered parts of the floors. Obsidian chips and points littered the floor surfaces and could be found two to three inches below. The third cave from the north contained broken pottery, cordage and feathers, along with a few half-buried bones. Recent irrigation caused destruction of the caves, with the possible exception of the southernmost, which dredging of the water channel of the creek has made inaccessible.

On the east rim of the gorge, people still find obsidian chips and points, and on the less precipitous west slope, tilling sometimes exposes obsidian chunks and milling tools. Recent casual observation revealed several manos and one four by four by two centimeter chunk of fractured obsidian.

The altitude of the hillside site where artifacts occur is slightly lower than the 5,076-foot apex and an estimated ninety feet under the Bonneville level. Thin lake-related deposits overlay the Salt Lake Formation, and small explsures of conglomerates, obsidian- veined lava, and other large stones associated with the Salt Lake Formation can be seen. Obsidian deposits are rare in this part of southeastern Idaho. The only other obsidian-bearing rock found in Cache Valley is an igneous intrusion of essentially Hornblend dorite traversed with several dykes of obsidian, which lies eight miles southeast of Winder between Franklin and the divide north of Worm Creek. Small obsidian pebbles have been found along Marsh Creek to the northwest.

On this hillside, obsidian chips and points, interspersed with small, rounded pebbles rest on the ground surface in circular breaks, measuring 1.5 to 2.5 meters in diameter, between the sagebrush. The points are small and sometimes difficult to distinguish from the chips without close examination.

Nearby on the same hillside, two flat circular stones, nineteen cm. in diameter, were discovered in close proximity to each other. They were well-shaped and weather-worn. The purpose for which they were used is not clear.

Artifact-bearing sites are not unique to Winder. Similar sites are common throughout the region. A.J. Simmonds, in his history of Trenton and Cornish, mentions an Indian Cave

which yields arrow points, pottery fragments and charred animal bones. He also indicates that marshes near the two towns contain stone and flint artifacts.

The large cave in Smart’s mountain in Franklin is under excavation at the present time. Archaeology teams from Idaho State University evaluated Weston Canyon rock shelter, a few miles southwest of Winder, and a corresponding open hill site near Malad, both at elevations of about 5,000 feet in the late 1960s. The study reveals that two occupations at each site emerged at contemporary time periods. Radiocarbon determinations dated these sites at 7,000-5,800 B.P. and at 1,000 B.P. Evaluations suggest a close correlation to culture patterns common to the Bitterroot Cultures of the eastern Snake River plain to the north.

Battle Creek Fault Zone and Flood

Fault lines on both the east and west sides of Winder can be followed easily and have been mapped. A series of hot springs from which flows the hottest ground water (at 77º C. or 171º F.) found in Cache Valley is associated with a fault zone at Battle Creek.

The Winder Reservoir failure of 1911, a rain on snow event, further disrupted the archaeological evidence of the site, with its waters flowing south, down Battle Creek and into the Bear River.