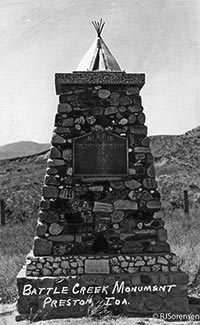

Battle Creek Monument

The History Behind the Making of the Battle Creek Monument

Beyond the words on the plaques of the Battle Creek Monument is a fascinating collection of stories represented by each of the stones used in its construction. Recorded meticulously by Myrtle Ransom Goff, chairwoman of the monument committee, and secretary of the Franklin County, Daughters of Utah Pioneers Camp, the stories reveal a wide variety of people, places and ideas.

D.U.P. members worked for six years to plan and construct the monument. They contacted senators, editors and government officials for their opinions on the wisdom of such a marker, the funding needed, and production details. Local D.U.P. camps invited similar camps around the intermountain west to be involved.

When the monument was dedicated amid much fanfare in 1932, in honor of both the soldiers and the Indians who died there in 1863, the highway ran to the east of the monument. The roadway changed when the current highway was constructed.

Boy Scouts of America, D.U.P. camp members and historical societies around the nation were invited to send in stones. The organizers wanted rocks from diverse places throughout the nation, plus the histories and reasons why that particular stone had been chosen to become a part of this structure.

The intention is to have the monument contain a human interest because of your participation. Gather where you will, adding what interest you can,

stated an article in the August 3rd, 1932, edition of the Franklin County Citizen. As the contributions came in they were displayed in the windows of a downtown busines. The notes carefully catalogued by Goff.

The stones had started arriving from the tops of mountains, the foundations of buildings, homes and cemeteries. Some had connections to Native Americans, having been found in an Indian camp or the site of some other battle. Some represented geologic history and others social history. This piece of petrified wood may have come from the Glencoe area.

At least 416 stones were submitted each one numbered, and found a place in the monument. Not all of the copies of the notes were legible, some were very detailed, and many seemed to represent a family. Many were sent by descendants of someone involved with the battle in some way, such as the family of William Dees, a settler who knew the Indian language and was instrumental in bringing about peaceful situations several times.

This rock is from a grandson of a woman who carried food to the wounded soldiers at Franklin after the battle,

read one note. This is from Soldier Bridge, built by General Conner for the transportation of his soldiers

read another. Many stones came from people who lived, or had lived, in Battle Creek when it was a community, their notes citing the business they had operated– a hotel or a warehouse.

Other rocks traveled quite a distance, from Alaska (not a state at the time) to New Zealand pumice stone picked up in 1920 at the Maori Agricultural College. One little round one picked up from Hudson Bay trading fort during the early history of Canada,

another from The Hill Cumorah in New York, and another from Spring Hill, Missouri, site of Adam-ondi-Ahman.

Several arrived from California, Monteray, Catalina, the Society Islands. There is a rock from the banks of Niagara Falls in New York and another from the Allegheny Mountains in Pennsylvania. Quite a few came from the walls of mines in Butte, Montana; the Conda mine around Soda Springs; the Cooper Queen Mine near Malad; the Winward Placer Mine; the Mercer Mine in Mercer, Utah; copper from the International Smelter at Tooele; and one from a Kennecott mine in Alaska.

Rocks that were connected to the Native Americans involved in the massacre included grinding stones, one was from Rocky Canyon the pass used by Indians going from Cache Valley to hunting grounds in Gentile Valley, and several from Fort Hall, Idaho, the nearest Indian Reservation. From Lookout Mountain in Tennessee came an arrowhead and a hatchet head. A heroine of the west, Sacajawea was represented with a rock from the Blue Mountains of Oregon.

Several represented incidents where the lives of white men were taken: in 1862 a band of pioneers were surprised by the Shoshone, killing nine whites and leaving six wounded at Massacre Rocks on the Snake River. An incident from Ryan’s Canyon in Montana was recalled; a stone was sent from the Blackfoot River where a Mr. Hull was killed in 1891.

Geologically interesting stones included petrified wood from Arizona, petrified juniper from the Glencoe area of Franklin County. A piece of dinosaur bone was delivered from Vernal, Utah and stone #355 was a petrified pelvis covered with petrified shells found in the Bear River Narrows.

The two largest categories of stones would be those from various places in Franklin County, Gentile Valley and Cache Valley, chosen by families or Scout troops, and then those that were connected with local history. Many came from quarries used by the early settlers for important buildings. Several were from temple hills: the Logan and the Manti L.D.S. temples in Utah.

Another large group came from the foundations of early settlers’ homes and church meeting houses from Salt Lake City and the villages along the route north to Battle Creek. Families of men who had served as guards on Little Mountain or Mt. Smart in Franklin’s earliest days sent in their donations.

The railroad days of Battle Creek were represented with a stone from the Round House there and one from Corrine, Utah, another railhead terminus in those days. A stone from the Oneida Stake Academy quarry came, as did one from the grave of Martin Harris in Clarkston, and one from Weston’s castle rock, which stands along the trail used by John C. Fremont in his explorations in 1843-1844. A Providence Vanguard troop submitted a rock from a wall of the first lime kill (sic) in Providence Canyon. This kiln furnished lime for the early settlers and started to operate about 1860.

Likely this kill

was a kiln, used for the calcification of lime to be used in the mortar of the pioneer homes.

Two or three stones originated around Red Rock pass near the headwaters of Marsh Creek, part of the famous ledge that was the retaining wall of old Lake Bonneville. When that wall gave way the waters rushed to the Snake River and the Pacific Ocean and all that is left is the Great Salt Lake,

so said the note accompanying the pebbles. One sedimentary rock from Logan Canyon showed the imprint of seaweed, and was touted as at least 5,000,000 years old.

Another was around a small, elliptical, smooth rock found in the nest of a mourning dove in Logan Canyon- the note stating that the bird had thought it was one of her eggs. Ages of time have changed the area where this monument stands, each stone a record of an era that has ended.1

Notes…

- Daughters of the Utah Pioneers Notes on the Bear River Massacre and Site, in the Franklin County Citizen, 1932; Scrapbook of Battle Creek Monument, compiled by Myrtle R. Goff.