Pioneering the West

I was a lad of seventeen summers when the Sweeten boys came and told me the new Reeves plow engine had arrived and (was) standing on the railroad siding at Malad City, Idaho. I begged mother to let me go with them. To see the big engine unloaded would be the greatest thrill of my life, I was sure. So mother reluctantly consented and carefully packed a grub box with a bundle of clean underwear and shirt. What joy and rapture filled my bosom as I sat with the boys in the new white top buggy and we drove in a northwestern direction. We arrived in the terminus city about sundown and drove down to the track where the brightly painted in rich brown black, yellow and green monster stood, with the enchanting engraving of the front smokebox door— Reeves & Company, Columbus, Indiana.

Regretting it was too late to begin the unloading that day, we went to the town restaurant and hotel and met Mr. Evans, the expert, direct from the factory. What a wonderful man and such a pronounced character. I never expected to be privileged to come in direct contact. The older Sweeten boy introduced me as their engineer, which sent a magnet of pride through me as the eastern man said with uncertain assurance he thought he could soon teach me to drive the new machine and made some casual remark about the town being the wildest he had entered for some time.

Malad City was a frontier settlement and at one time a way station on the Oregon Trail when the overland express made its regular trips and the pony express changed saddle horses for the rugged climb through the Rockies. Some of the old settlers yet delight in telling of the massacres and hold-ups of the stealth-full red man, as well as the common practice of road agents robbing the stage. Such stories could be easily believed by strangers, as they saw such suspicious looking charters, and the typical American Indian of the Shoshone tribe walking the streets. Yet the townspeople boasted of their advanced civilization since the railroad had reached their town and was no longer isolated from modern traffic and a salesman or factory-man was quite an ordinary person to register at hotels.

We slept in Palmer's barn, an old historic station in the days of stagecoach. The factory-man delighted in entertaining the boys with suggestive obscene stories until I ventured to remark that I did not think his stories very uplifting, which seemed to change the trend of thought to more wholesomeness and my courage seemed to take a firmer grip and I asked him all about the factory and the manufacture of such ingenious things as a steam engine. We talked until the crimson light of dawn on the eastern skies began to show through the opened door in the hayloft and the usual quality of snoring sounded from the other boys was evident they had fallen into the valley of dreams.

My new friend showed signs of fatigue and his answers to my questions came weaker and weaker until he too joined the others in their slumbering chorus. I didn't sleep a wink and as soon as the spring morning began to break on the old historic town I quietly slipped down from the hayloft, feeling sure not another soul was awake within miles. As I stepped from the ladder on the barn floor a gruff voice, which almost scared me stiff, said Where you going lad?

It was the stable night watchman.

Thank goodness it was not a tramp. He tried to discourage me and told me to go back to bed until daylight. But I could no longer stay away from that beautiful shiny engine on the flat car. It was quite a walk to the siding. The stillness of the morning air seemed weird and several times I thought I saw Indians and stage robbers spring from behind buildings and tall sagebrush.

On reaching the object of my profound interest I opened the fire-box door and took out the box of shiny brass fixtures and placed them on the boiler properly. With cotton waste I shined them up until the rising morning sun made them fairly glisten. It was the most beautiful sight I had ever beheld.

With borrowed hose I reached the nearest outlet and filled the spacious boiler until it showed the proper level, and then built a wood fire to slowly heat and raise the temperature. I watched for more than an hour and rising steam. I so wanted to sound that beautiful chime whistle and finally when sufficient pressure was raised, I tried to awaken the slumbering Welch city.

It was ten o'clock when everything was ready for the decent, with a runway made of ties and other timber; a gradual decline was built from flatcar to the ground. Mr. Evans, the Reeves expert, showed skill and a steady hand on the throttle as he slowly drove the beautiful monster and safely landed it on western soil before a crowd of skeptical mountaineers.

We started in a western direction and reached the summit separating the Malad Valley from the Curlew, after considerable difficulty with breaking through culverts and being stuck in the mud, caused from the heavy spring rain we encountered. The beautiful work of art on the finished product was somewhat smeared and soiled with the Malad clay, much to my disgust and sorrow.

The storms had abated and the clear blue sky with the various colored rainbow in the east furnished a most picturesque sight from the summit as we turned to look back over our difficult trail and I marveled that nature could be so kind to that criticizing growl of townsmen we had left behind.

Slowly and steadily we descended down the rugged Ireland Canyon where nothing heretofore had been seen of the modern steam age, except an Aes Portable steam engine for sawmill purpose had been hauled by mule team into the famous Bull Canyon some years previous.

The white faced Hereford cattle with the Bar-M brand took fright, throwing their tails over their backs, ran for shelter. The lowly coyote was seen on distant slopes traversing its course at the sight of the curious monster. A few migrating Indians with their traditional superstitions, kept their distance to the far side of the mountain pass. At the sound of the chime whistle echoing through the canyon all was turned to turmoil and weird fright.

The cattlemen and sheepherders gave us a significant black look that showed no signs of welcome. The Bar-M and Mule Shoe eastern cattle syndicates were very reluctant to give up the range and a hostile feeling existed between herdsmen and settlers, but a worse feeling between sheepherders and cattlemen. A lonely cabin beside a trail would be shrouded with mystery from a shooting scrape and tales of such kind were commonly related by early settlers. The air was blue in the Curlew Valley, which seemed to be a peculiar part of this particular location.

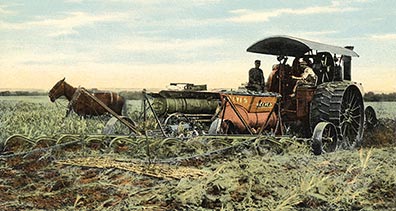

The modern steam power was soon put into service and a sage-grubber that had been invented by a rancher, cutting a twenty-four foot swath was drawn behind the thirty-two horsepower engine and then followed up with twenty-four gang-plows so the clearing of the native heavy growth was rushed with marvelous speed. I had acquired the art of steering and the Sweeten boys appreciated my services and engaged me for the summer, much to my delight and joy my dreams and aspirations were now being realized. Taking delight in rising early to fire up, for which the boys raised no objection.

But alas how soon was my hopes were blighted, when I caught sight of my elder brothers coming with the old blue and bay mares, hitched to the white top buggy and my pleading and begging, as well as that of the Sweeten boys and promising me good wages was to no avail and I was loaded in the buggy and hauled down to lonesome Bannock to spend the rest of the summer following a hand plow, or foot burner. So much of a contrast to the beautiful Reeves engine, I wept with tears, my hopes had been so blighted.1

Notes…

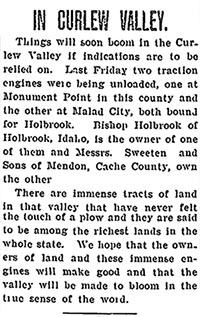

A self penned article, of L.K. Wood's thoughts on the arrival and unloading of a shinny new Reeves & Co. plow engine, at Malad City, Idaho. The date would be in the early spring of 1907 according to the date of the newspaper article and the shiny new traction engine belonged to Robert Sweeten and his sons. Heber A. Holbrock, Robert's son-in-law bought an engine at the same time, His was driven up to the farm from the Momument Point siding, near Locomotive Springs on what was then the Southern Pacific Line.

The Joseph T. Wood family lived near Robert Sweeten's place in Mendon being one-half block to the west. The Sweetens wanted bigger farms and more opportunity for their growing families, so they took up new land in the Curlew Valley, twenty miles or so, out west of Malad City, Idaho. Holbrook was the town that grew up in the valley as the main residence of many of these new pioneers of the virgin native grasslands.

The town was named after Heber Angell Holbrook, the first bishop of the place and a son-in-law to Robert Sweeten. He married Robert Sweeten's oldest daughter, Martha Emma Sweeten in 1893. With both sons and daughters needing to make a living and thus farms of their own, there was just not enough land in the Mendon area, to support the growing needs of Robert Sweeten's now extended family. After his wife Amanda H. Sweeten passed away, in March 1903, there was nothing to keep Robert in Mendon. They rented the Mendon farm, and latter sold some of it to the local residents of town. Mormon D. Bird rented the Sweeten home for a time, and a large tract of land, for the time from the family as well.

L.K. Woods' family also took up new farms out to Bannock as the Mendon people call it. Bannock to them, extended from Arbon, Idaho down through the Curlew Valley, Pocatello Valley and even into Blue Creek and Hansel Valley in Box Elder County in Utah. Heber George Wood, L.K.'s older brother moved and lived out toward Arbon. There was even a town, now just a forgotten place, called Buist, north of Holbrock on the way to Arbon, Idaho. A lot of Mendon and Cache Valley people settled out there.

- Pioneering the West, L.K. Wood.