Andrew Bigler ~ Index

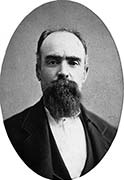

From 1875 until his death in 1893, Andrew Bigler was one of Mendon, Utah's most prominent and active citizens. Born in West Virginia in 1836 he came to Utah with relatives when quite young, living in Davis County until about 1872, when he moved his family, consisting of his wife (Loretta H. Smith Bigler) and five children to a farm in Box Elder, County near the present site of Collingston.

In 1875 he moved to Mendon, Utah, his home until his death. He was a man about six feet in height, well set-up, strong and active, however, not fleshy and was a fine specimen of physical manhood. In disposition, he might be termed quick tempered and outspoken, fearing no man, yet was courteous and gentle to all. He had little chance for schooling when young, however, by reading and the association with worthy people he became well informed in matters of history. He was a sociable man and young people were always made welcome at the Bigler home by brother and sister Bigler and their family, therefore it was a gathering place for all.

Early in life Andrew Bigler fulfilled a mission to Texas, for the Latter-day Saint church.

After Mr. Bigler's discharge from Civil War military service he returned to Mendon, Utah, where he lived the remainder of this life. He engaged in general merchandising, owned and operated a molasses mill for a year or two and was active in almost every undertaking that benefited the community. He devoted many years to breeding and training race horses, which occupation proved successful. He purchased and brought to Mendon in 1878, the first draft stallion, a Norman weighing 1600 pounds, to reach Cache Valley, which was of inestimable value to the whole county. In handling horses, Mr. Bigler was an expert, few equaled and none excelled him in northern Utah. He also assisted in the buying and improving of cattle for the townspeople.

Civil War Service

Andrew Bigler, who was born in Clarksburg, West Virginia in 1836 was twnty-six years old and living in Mendon, Cache County, Utah when he responded to a call from Brigham Young to help form a Utah Cavalry unit to defend the Overland Trail. President Young was acting upon the request from President Abraham Lincoln to organize a company of cavalry to serve for ninety days and to provide protection to the Overland Route. That route was vitally important to continental communications for the Union, as the telegraph lines and mail delivery relied heavily upon it.

President Young mustered the volunteers on April 28th, 1862 with the following details and qualifications for service. Solders volunteering were to equip themselves, as well as to provide their own horses, saddles and firearms. President Young stated that he wanted only worthy and righteous men to enlist. He further stipulated that they were to abstain from card playing, dicing, gambling, drinking, or swearin~ and should be nice to their animals. In short, they should be worthy of great praise. The men were directed to have prayer every morning and evening of each day, that they may receive the protection of the Lord.

A Utah folk hero, Captain Lot Smith was called to be the leader of the company which consisted of one-hundred and six men. Captain Smith had previously been a Major in the Nauvoo Legion and achieved fame in Utah for disrupting the progress of Johnston's Army as it advanced upon the Utah Territory, in 1858. His company was organized in the following manner: 1 captain, 2 lieutenants, 1 quartermaster, 4 sergeants, 8 corporals, 2 musicians, 2 farriers, 1 saddler, 1 wagoner with the balance of 80 or so being privates. Andrew Bigler, considered to be an expert horseman, was made a corporal which made him responsible for about ten other men.

The march to Independence Rock, (located in present day South Central Wyoming), was not easy. Shortly after leaving Utah, the company encountered heavy snow with drifts ten feet high in some of the canyon passes they had to go through. It was cold and wet and difficult for the horses to break through the heavy snow. Later the troops ran short of supplies, which made it even more difficult to move ahead rapidly. Many times they were faced with crossing rivers and streams in muddy or frozen conditions. They also encountered problems with the Indians who had destroyed some telegraph lines and had intercepted and destroyed some of the mail. Conditions were challenging, with adverse weather and meager food rations, but never did these men complain. They forged onward with relentless persistence.

After twenty-six days, the company arrived at Independence Rock, which became their headquarters encampment. There was no significant military action while they were there, only a few skirmishes with Indians, intent on damaging the telegraph lines or stealing horses. However, the presence of the cavalry there, was undoubtedly a deterrent to any thought the Confederacy may have had of gaining control of the Overland Route. The only fatality occurred through the accidental death of a young private, who drowned during a river crossing. Otherwise, all returned safely back to Utah, arriving back one-hundred and seven days after their departure.

Andrew Bigler was discharged from service as a Union Cavalry soldier on August 15th, 1862. Upon the return of the cavalry, President Heber C. Kimball, of the First Presidency of the Church said that, Their service was a sign of loyalty and love of the Latter-day Saints for the United States and that they had saved Israel with their service.

It was indeed an act of loyalty to the United States and the Constitution, as well as a defense of the Overland Route. President Brigham Young stated that he viewed those serving as loyal, obedient, patriotic and thoroughly American.

Each soldier received wages for their military service. Upon their discharge, the company in total, earned more than $35,000. The entire amount was turned back to Governor Brigham Young, which, no doubt was a great boost to the cash starved economy of Utah.

Andrew Bigler returned to his wife and children in Cache Valley where he was engaged in farming. He was well respected and was successful in his business operations. He died in Mendon, Cache County, Utah on 8th January 1892 at the age fifty-six.1

Civil War Service with Lot Smith

In 1862 he enlisted in the United States Army and served as a Corporal under Captain Lot Smith and went east into Wyoming to protect the overland U.S. mail route from Indian attacks and depredations. The men furnished their own horses, bridles, saddles and all equipment necessary for the services, at their own expense, something otherwise unknown in the history of the Civil War. Many were the hardships endured on that memorable campaign.

On Wednesday April 29th, 1862 the company moved to the south-east part of the city where they were organized and each man sworn in as a soldier of the United States, May 30th. The company moved to Parley's canyon where President Brigham Young addressed the troops. General Daniel E. Wells accompanied the President. I desire of the officers and privates of this company that in this service they will conduct themselves as gentlemen, remembering their allegiance and loyalty to our government, and also not forgetting that they are members of the organization to which they belong, never indulging in intoxicants of any kind, and never associating with bad men or lewd women, always seeking to make peace with the Indians. Aim never to take the life of a white man or an Indian, unless compelled to do so in the discharge of duty, or in the defense of your own lives, or that of your comrades. Whenever and wherever you can hold councils with their Sachens, or peace Chiefs, do not fail to embrace the opportunity and thus win their friendship and prevent the shedding of blood if possible. Another thing I would have you remember is that although you are United States Soldiers, you are still members of the church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints and while you have sworn allegiance to the constitution and government of our county, and have vowed to preserve the Union, the best way to accomplish this high purpose is to shun all evil association, and remember your prayers and try to establish peace with the Indians, and always give ready obedience to the orders of your commanding officers. If you will do this I promise you, as a servant of the Lord, that not one of you shall fall by the hand of the enemy.

Going by way of East Canyon, the company camped at Kimball's Ranch, leaving there they moved to Chalk Creek where they had to build a bridge. They traveled on down to the mouth of Echo Canyon where they found the bridges across the streams not strong enough to hold their wagons, hence, built a bridge on which the men crossed pulling wagons, the horses swimming the river. Day by day the men moved, crossing Bear River and on May 11th camped in sight of Fort Bridger, Wyoming. They saw the Stars and Stripes flying over it, but as the troops approached, the flag was taken down for the people at the Fort thought they were Indians approaching.

On May 12thh, they camped at Smith's Fork. On May 17th they had reached the Little Sandy camping at each place only long enough to get a few hours rest for both men and animals. The weather was cold and some snow fell. On May 20th, they entered a mail station, found the mail bags had been opened and thei contents scattered through the house and yard. They also found a stage that had been attacked and stripped of its load. Here they received a report that the Post at Devil's Gate was burning and for the first time they were ordered to have their arms and ammunition ready.

At Plaunt's Station they met the Burron command. Here they set up camp, raised the flags of the United States and each day were called out to drill. This was in the vicinity of Devil's Gate. Teams were sent into the mountains for timber and plans were laid to build a house and corrals. May 28th found them all busy, as one diary says The cross cut saws are busy, axes are busy, shovels and spades are in great demand.

A large bake oven was built.

On May 29th, a telegram was received from Brigadier-General Craig to start fifty men towards Ham's Fork at which place Indians had stolen some horses. Captain Smith started immediately, taking with him three officers and fifty men. The month of June was spent in camp. General Craig came to the station and directed them to call upon his quarter-master for supplies if they were needed. They met some of the Latter day Saint trains bringing emigrants from the east and gave them what help they could.

A telegram dated from South Platte was sent to President Brigham Young from Captain Lot Smith on June 24th, 1862. Camp Independence Rock I had an interview with Brigadier-General Craig, who has just arrived by stage at this point. He espressed himself much pleased with our promptness in responding to the call of the general government, with the exertions we had made in overcoming speedily the obstacles on the road to reach this point and spoke well of our people generally. He also stated that he had telegraphed President Lincoln to that effect and intended writing him at greater length by mail, and I received later word that he had placed the whole of Nebraska Territory under martial law. He also remarked that the Utah Cavalry were the most efficient troops he had in the service, and proposed to recommend that our service be extended an additional 90 days.

Respectfully, Lot Smith, Comm. Utah Volunteers.

Immediately afterwards orders were received that the command return to Fort Bridger and again Captain Lot Smith notified President Young as follows: North Platte, June 27th, 1862. President Young I have just received orders from General Craig through Colonel Collins to return with my new command to Fort Bridger to assist in re-establishing the mail and telegraph lines and stations from Green River to that point. Lieutenant Rawlins and command arrived here yesterday. Owing to neglect of mail carriers, Lt. Rawlins did not receive my orders until eight days after they were due, consequently, there has been no detail left at Devil'e Gate. Lt. Rawlins left the station in charge of Messrs. Merchant and Wheeler, traders, who formerly owned the station that was recently destroyed by the Indians. This place is subject to our orders at any time. Col. Collins has shown himself a wise and efficient officer. He is decidedly against the indiscriminate killing of Indians, and will not take any general measure against them, save on the defensive, until at least he is aware by whom the offenses have been committed, and even then, not resort to killings until he is satisfied that peaceful measures have failed. Col. Collins and his officers declared that we are the best suited for this service, both men and horses being used to mountain life and knowing well the habits of the Indians. We have been assigned to Col. Rollin's regiment. General Craig's Division.

I am yours respectfully, Lot Smith.

The command made immediate preparation to return too, and were on their way back to Fort Bridger, Dr. Seymour B. Young in volume 25 of the Improvement Era, presents the story of Bear Lake Expedition, one of the most notable made by this group of soldiers.

Bear Lake Expedition

On the return of the volunteers from the North Platte to Fort Bridger, July 2nd, 1862, preparations were made for a general inspection of the lines of mail and telegraph stations, with a view of placing them in perfect condition preparatory to our return home August 1st, 1862, as the term of our enlistment expired on that day. However on the night of the 3rd of July, five soldiers belonging to the U.S. Cavalry Company, stationed at North Platte, took it to their heads to desert, and with horses, saddles, blankets and side arms, they succeeded in leaving the camp in the dark hours of the night without being discovered. On the following morning it was found that their tracks pointed to a westerly direction. Col. Collins immediately telegraphed Sergeant McNeil at Fort Bridger, informing him of the desertions, with a request that he watch for and apprehend these deserters. When the message reached the Fort, the Sergeant was soundly sleeping from the effects of too much fourth of July, but in the afternoon he was aroused, the message submitted to him, and he at once applied to Captain Smith for a platoon in readiness to take up the march numbering eleven men, including the U.S. Sergeant. Before leaving camp, however, Captain Smith gave the following instruction to Lt. Knowlton that while he was making all necessary efforts to trail and capture the deserting troopers from Col. Collins command, he seeks to discover the location of Chief Washakie, who was supposed to be camped somewhere on the southeast shore of Bear Lake and instructions were given to have a friendly talk with the Chief of the Shoshones, and induce him, if possible, to call home his young Indian warriors and prevent their participation, with other hostile Indians, in making raid upon the emigrant trains and destroying the government mail stations and telegraph lines of communications across the continent, and counsel his young men to cease their war upon the white people generally. Leaving camp about sundown, July 4th 1862, we took up our line of march and made out camp for the night at Yellow Creek.

On the following morning we resumed our journey, following Yellow Creek to where it joins Bear River. Farther on, we arrived at Smith's Fork of the river, and crossed this tributary on a toll bridge, after riding through the overflow of the stream for several hundred yards until we reached the eastern terminus of the bridge. After paying the mountaineer fifty cents for each man and horse, we were allowed to cross. Sergeant McNeil declined to go farther with the party as he had learned from Lt. Knowlton that we intended to make the circuit of Bear Lake Valley, and that meant the swimming of the Bear Creek several times, and he claimed he could not swim; consequently, requested that he be left at the bridge at the mountaineer's home. When we returned from the expedition from Bear Lake Valley he would gladly join us and accompany us back to Fort Bridger. Lt. readily granted his request and the following morning we proceeded on a westward course along the Bear River, reaching Thomas Fork, another tributary of the Bear River, we halted and made preparations for swimming this swollen mountain stream, here we gave some assistance to a company of emigrants on their way to the Snake River country and Oregon, in their efforts to establish a line across the river to pull their luggage and wagons over by the aid of a wagon box for a ferry boat. The volunteers then proceeded to swim with their horses across the stream, and on the west bank unsaddled, turned their horses out to graze, while the men dried their clothing in the sun and prepared to eat a dinner of hard bread and a cup of cold water.

A lone Indian suddenly appeared sitting on his pony at the top of the bluff near our encampment. Lt. Knowlton made signs for him to come down and see us. Accordingly he responded and when he arrived in camp we found he had been out on a hunt for game and he had succeeded in killing antelope, which he had lashed behind his saddle. Our interpreter made a proposition that he (the Indian) furnish meat for our dinner, and we would furnish the bread, and he was to eat with us. He took the carcass from his saddle and delivered it to our cook who proceeded to cut and slice from the hind quarter and the loin of the antelope enough choice meat to make a dinner for eleven hungry men, the Indian included.

Dinner over, we returned the balance of the antelope to the Indian, saddled our own horses, mounted and resumed our journey, advising the Indian to pilot us to his encampment. This he refused to do, however, with a little persuasion with the exhibition of a loaded revolver, convinced him that it would be very necessary for the white man to have his way. Accordingly, we followed him to the vicinity of the Indian camp near the present location of the town of Montpelier. Of course, this was a barren plain then, with no sign of a white man's habitation visible in all the Bear Lake Valley.

Approaching the Indian camp, we saw a band of warriors mounted, swiftly riding in what is known as the War Circle. As we rode toward this circle we could hear their whoops and yells of defiance. We immediately ordered our Indian prisioner to ride at the forefront of our little group and shout to his red brothers that the white men intended peace not war. As soon as we came in hearing distance and seeing one of their red brothers in our lead making signs of peace, they immediately ceased their war circle and several of the principal men came riding toward us with a message that we would be permitted to enter their camp, an invitation which we accepted. We were a conducted to the council wigwam. As night had already set in, to show our fearlessness and to make believe our perfect confidence in the Indians, we immediately removed saddles, bridles, and ropes from our weary mounts and left them free to graze and mingle with the Indian ponies belonging to the village. Then after a hasty bit of supper from our mule packs, we spread our blankets in the open and lay down for a few hours of much needed rest, but none of our party slept soundly for they realized that the redmen outnumbered our party ten to one, and under our blankets during the night our hands were in close contact with our firearms. At break of day we arose and adjusted our clothing, ate hastily of a small ration of hard bread, sent two of the party out among the band of Indian horses to separate and bring in our own. In this they were entirely successful, and we soon fixed our bedding and baggage on our pack mules, saddled our horses and stood ready for the command to mount and away, and yet we waited for some kind of communication from the war cheif or leading men, as no word had been spoken to us by the Indians since we entered their camp at sunset the evening before.

The silence of the Indians to us seemed somewhat ominous and we began to look around for some kind of life among them. We soon discovered however that we were not the only ones awake and alert, for several Indians were observed closely watching our movements from behind rocks and willows on the outskirts of the camp. Lt. Knowlton made a sign, beckoning them to approach, and soon three or four young warriors with the medicine man of the village came. To these, the officer gave information that we were on our way to see Washakie, and he offered two of their young men each a shirt if they would accompany us down to the river bringing with them a skin lodge. With this we wished them to construct a lodge-boat to ferry our packs across the Bear River. The mention of the name of Washakie, the great Chief of all the Shoshones, seemed to change everything in our favor, and now we were quickly supplied with the desired help for crossing the river.

Here the Indians showed themselves experts in quiding the lodge-boat from the east to the west bank, laden with our packs and saddles. Steering for the west shore, we immediately swam with our horses in the wake of the boat across to the opposite bank, making the crossing in safety without losses. We paid the two Indians the stipulated price, namely, two shirts, thus filling our part of the contract, yet the Indians were not satisfied, they were no doubt hungry, for they demanded bread. The only rations we had left consisted of about eight pounds of hard bread crumbs. We divided these with the Indians and sent them away happy. Then we saddled our horses, packed our mules and started on an old blind Indian trail leading in a southerly direction, taking us through Bear River bottoms now covered with from two to four feet of water, the overflow of the tributaries of Bear Lake.

On emerging from several miles of wading, we reached higher ground at a point not far from where the city of Paris, Idaho, is now located, then we continued our march to the south on the trail leading us through a dense thicket of willows as high as the heads of our men, when mounted on our horses. Suddenly, we came to an opening in this dense willow-copse, of several hundred yards in extent, and found ourselves in the midst of a bank of hostile Indians, another of Chief Bear Hunter's band with whom we had camped the night before. Within this opening was the Indian camp, about twenty or thirty tepees and nearby was a band of Indian ponies grazing. Among the Indian horses, one of our party recognized a fine saddle horse belonging to Samuel W. Richards of Salt Lake City. Knowing the high value in which this animal was held by Brother Richards, and believing that the Indians had come by it dishonestly, Lt. Knowlton ordered Sergeant Spencer to rope the animal for the purpose of recovering it for its owner, then there was something doing. A hunched-back Indian rushed to the rescue of the horse, placed his knife against the rope a little way from the neck of the animal and was about to sever the rope when he was thrown to the ground by Spencer, rolling over several times when he struck the earth, but not being seriously injured. He regained his feet and rushed upon Spencer with his knife ready to strike, Spencer grabbed the uplifted arm and gripped it with such force that the knife fell from the Indians hand. The Indian was then thrown again with more violence and did not return to renew the fight, but skulked away into the willows. Suddently we saw the wickiups deserted and we heard the twang of bow strings and click of gun locks from hiding places and secure protection in the dense willows behind which the Indian skulked. Lt. Knowlton immediately gave orders for every man to dismount and each seek a separate path for himself out of the ambush, making way to open ground in a southerly direction. In this we were successful and thus escaped from the threatened attrack without loss or injury of any of our party.

Continuing our march to the south we came suddenly to a mountain stream known as Swan Creek, into which some of our boys rode in an effort to make a crossing, but the current was so swift that their horses were carried off their feet and thrown helpless upon the shore from which they entered the stream. We then discussed the propriety of going up or down the stream in search of a more favorable crossing place, when suddenly there appeared a lone Indian, approaching from the south, who proved to be friendly. He was from Cache Valley and immediately piloted us on a trail leading over a steep mountain spur around the head of the rushing stream and then pointing us to the trail leading to Washakie's camp, left us to pursue our journey. About sunset we arrived at the camp of the Snake Chief, were made welcome by him, and after finishing our small ration of hard bread crumbs, we rolled in our blankets and had a good, peaceful, uninterrupted night's rest.

On the following morning, Washakie was informed of our attempt to recover the stolen horse and he promised us that he would send one of his men to the belligerent camp in the willows, near Swan Creek, have the horse brought back to his camp, and if possible, find the Indian who stole the horse and have him punished. We learned after our return from the expedition that Washakie had taken the thief and given him a very severe whipping when he was brought into camp with the stolen horse. Remaining here the remainder of the day, Washakie discovered that we were without provisions. He brought from his wickiup about fifty pounds of flour. Laying it on the ground he said, as he drew his finger across the center of the sack, This part is for you, and this part is for me and my papooses,

thus dividing the flour with us equally with his own family.

We immediately set to work making and baking bread and with plenty of fish, with which we were supplied by the Indians, we partook of a square meal the like of which we had not had for two or three days past. The following morning, July 10th, we left the camp of our friend Washakie, taking by his request a near relative who appeared to be in the last stages of tuberculosis, to give him and his squaw safe escort to Fort Bridger, where he hoped to be benefited by treatment by the post physician. Two young Indians accompanied us, bringing with them a new skin lodge, with which to ferry the sick man, his squaw and our packs and camp outfit, across the Bear River. On arriving at the crossing, we assisted the Indians in constructing a lodge-boat on which the invalid and luggages of our camp was safely carried across the river. The troopers swam the river with their horses. This crossing was made without incident or loss and immediately our march was taken up to headquarters at Fort Bridger, where we arrived safely on the evening of July 13th, and the full account of the expedition was given by Lt. Knowlton, to Captain Lot Smith who had expressed some anxiety in the last three days for the welfare of the expedition. When we left camp on the fourth of July we only carried rations for five days, and of course Captain Smith, being aware of this fact, looked for our return, but he made this remark to comrades in the camp who inquired about our extended absence, that, surely some one or two of the party would get out alive and soon make a report of the results of the expedition.

Our party brought safely to Fort Bridger the poor sick man and his squaw who had been committed to our care by Chief Washakie. Our report concerning our interview and final arrival at Washakie's camp, his warm friendship and acts of kindness expressed to the party with safe conduct of his relatives to Fort Bridger was the final report of the expedition that left headquarters on the fourth of July, under Lt. Knowlton, for the purpose of capturing some deserters from Col. Collins on the north Platte. The expedition so well planned and executed was a subject on congratulations from our commander. Although we did not find the deserters, we did find Washakie, the great Shoshone Chief, and on our return trip we picked up Sergeant McNeil, from the bridge at Smith's Fork, and brought him safely back to Fort Bridger.

The visit to Washakie, and obtaining his counsel and friendship, was in strict accord with the advice given by President Brigham Young, when he spoke to the officers and volunteers in Emigration Canyon as they were leaving Salt Lake City to engage in the service of the Civil War.

The Snake River Expedition

On the night of July 15th, 1862, a small band of Indians visited the ranch of Jack Robinson, one of the oldest mountaineers inhabiting the Bridger county, his camp about six miles above the Fort. They succeeded in running off upwards of three hundred head of horses and mules, of which number thirty returned the following morning. Captain Smith with his command was encamped near the old Fort and was notified by Mr. Robert Hereford, son-in-law of Jack Robinson, of the theft of the mountaineer's animals. Immediately after the bugle call, boots and saddles were in order, and in about three hours time, sixty men, including Mr. Hereford, were mounted and ready for the chase. There were ten pack animals carrying the camp outfit and general supplies, with ten days provisions. The following is a list of the names of the expedition:

Captain Lot Smith, First Lt. J.S. Rawlins, Second Lt. John Quincy Knowlton, Wagon Master Salomon H. Hale, Sergeants S.W. Riter, Howard O. Spencer, Corporals S.B. Young, W. Bringhurst, Newton Myrick, Andrew Bigler, H.B. Clemens, Privates Joseph Goddard, L.A. Huffaker, Jessie Cherry, Landon Rich, Thom Harris, Wood Alexander, E.M. Shurtliff, James Sharp, Tom Caldwell, Theodore Calkins, John Cahoon, Mark Murphy, Joseph Fisher, Albert Randall, Henry Bird, William Longstroth, William Lutz, William Grant, Hyrum Kimball, Peter Corney, E.A. Noble, Isaac Atkinson, H.B. Simmons, Daniel McNichol, Lewis Osborn, E.M.Weiler, Joseph Terry, Charles Burnham, George Cottrell, A.S. Rose, Lachoneus Barnard, Robert Hereford, J.M. Hixon, William Thoades, Hugh D. Park, Jimmie Wells, Lars Jenson, James Carrigan, Edwin Brown, John Arrowsmith, Frank Cantwell, Moses Gibson, John R. Bennion, Samuel Bennion, Jimmie Larkin, James Green, James Finlay, Francis Prince, William Bess and Reuben P. Miller.

The tracks of the stolen animals indicated that the Indians had taken a north-westerly course which the pursuers followed for twelve days, going as far as the head of the Snake River Valley, near the three Tetons, about 135 miles north-east of Fort Hall. Their first ride in the afternoon was thirty-five miles to the Muddy, through which the company had to swim and drag their pack animals with ropes, submerging the packs, provisions and clothing. The Indians, in their hasty flight, here abandoned two ponies and three of the stolen colts.

Second day… the company started at daylight, passed an abandoned mule, traveled fifteen miles and breakfasted at a small spring. Three miles farther they crossed Ham's Fork where, from the tracks of the animals at the crossing the Indian appeared to have had great difficulty in keeping together their booty, three more colts had been abandoned. The company swam with their animals over the Fork and traveled seventeen miles before dinner. After resting their animals a couple of hours they resumed their march and made thirty five miles, arriving at Fontenelle, a Fork of the Green River, five miles north of Sublettes cut-off.

Third day… started at daylight, and rode eighteen miles before breakfast, traveled twenty five miles farther, stopped to take dinner and rest the animals on an island of Green River, five miles below the Lander road. During this ride they found the first camping place of the thieves, since they had left Bridger, where the Indians appeared to be as far in advance of the pursuing party as at the start from Bridger. They having kept thus far in advance suggested to the soldiers the necessity of preparations for a longer expedition than was contemplated at starting. Accordingly, Captain Smith and Lt. Knowlton rode ahead to the Lander cut-off, to a camp of emigrants to obtain provisions, but they were unsuccessful. The expedition afterwards came up and continued on fifteen miles before camping for the night. In conversing with the emigrants it was ascertained that on the Thursday previous the Indians had stolen four animals from an emigrant train bound for the Salmon River. Seven of the emigrants followed them, and had a flight, resulting in one of the white men being killed, and three wounded. Nothing was recovered. On the night preceding the arrival of the expedition, some Indians attached an emigrant train, wounding one man, stealing the horse and some articles.

Fourth day… The expedition rested their animals in the morning during which time Lt. Knowlton, Seymore B. Young and Solomon Hale returned to Lander Road and tried to purchase provisions from another train of eight wagons, but could obtain none. The emmigrants refused to furnish anything, though the boys were willing to pay them any price. In fact, the style of the emigrants was anything but complimentary, underlying which was something like suspicion that the expedition was probably connected with the Indians who had attacked the immigrants already noticed. Broke camp at noon and marched thirty five miles and camped on a small stream near the base of the Green River mountains. On the way, we came upon a camp that had been suddenly abandoned by the Indians, in which we found a good deal of fat beef, the remnants of five oxen, but having apparently been too long exposed to the hot sun, was unfit for use. The Indians evidently had been surprised as there were evidences of a sudden departure and indication of a fight. Among other things, an emigrant cap was found lying on the ground perforated with bullets.

Fifth day… Started at daylight and traveled twenty-one miles, crossing the north fork of Green River. Rested two hours, here was another animal abandoned. Five miles farther struck the south fork of Green River. Crossed the other side and traveled thirty miles down the stream over a fearfully rough road. The trail taken by the Indians here was over landslides, rocks and loose stones, some places hundreds of feet above the river, where one misstep would have sent horse and rider into the stream. On this trail, the company found evidences of other thefts, such as the tracks of other American horses, mules and cattle. This justified the conclusion that the original band, pursued from Bridger, had gathered strength in numbers during the flight. By taking such a direct route, the red men probably intended to mislead the pursuer into the belief the Crow Indians had been the agressors. But for this, the Indians would certainly have taken another trail than the dangerous one passed over during the day. The expedition swam the main fork of the river and camped for the night. From the freshness of the tracks, and the remnants of a sage hen, the Indians seemed here to have been not more than six hours ahead of the expedition. An abandoned white horse was foung there. At the end of the days march on the twenty first day of July, a council was called and officers and men agreed that the company was too large and that with a smaller allotment of men it was believed they could make better progress in pursuit of the Indians. On inspection it was found that about twenty horses were lame, for the reason that they were unshod when they left the camp at Fort Bridger, and their feet had become exceedingly tender and sore with the constant contact of the gravel and rocks over which they had passed during the five days hasty march. Consequently twenty disabled horses, with their riders, were ordered to return to camp near Bridger, these troopers in charge of Lt. Rawlins, there to remain and await further orders.

Sixth day… This morning the smaller division of our command in charge of Lt. Rawlins broke camp and after bidding goodbye to their comrades, who were to continue their journey north under Captain Smith, they began their return march to the encampment near Fort Bridger. After starting, this portion of the company on their return to the main body of the command, traveled ten miles through a very rocky, thickly-wooded canyon and continued eight miles farther to one of the tributaries of the Snake River. Here we found two young colts, two mules, and other colts farther down the stream, all of which had been abandoned by the Indians in their hasty flight. These mules in possession of the Indians had probably been stolen from some immigrant company, for they were not of the Bridger stock.

Seventh day… The portion of the command under Captain Smith continued following the trail of the Indians which led over the divide on a chain of mountains from which issued the head waters of Green River and Wind River, the Wind River flowing from the east to this divide, and the Snake River to the west. The trail of the Indians turned westward, following the tributaries of the Snake River. On the 24th day of July, the trail led us through an elevated mountain valley with altitude, supposed, between seven and eight thousand feet above sea level, and through a dense forest of beautiful pine timber, reminding us of the celebration of this glorious pioneer anniversary day, in years gone by, at the headwaters of Big Cottonwood Canyon. From here the march continued the course of the Snake River being followed which became larger and larger as we struck the lower mesa and valleys of the Teton range. No halt was made, however, in this beautiful glade of timber, as we were led to believe, from the signs on the trail, that we were going closer to the Indians who seemed to be crowding their band of stolen horses to the limit. They no doubt realized that we were beginning to gain on them. At this stage of our march our provisions were nearly exhausted, and the company was placed on less than half rations, but yet we pressed on regardless of the pangs of hunger that were being felt, for we were in hopes of overtaking and capturing the Indians before they reached the crossing at the Snake River. On the 25th day of July, we struck the main canyon of the Snake River, continuing on the trail leading us in a westerly direction over the steep ledges and rocks hundreds of feet above the whirling torrents, where one misstep of the horse would have sent the rider and horse into the foaming river a thousand feet below. Here the trail showed more evidence of other thefts by the Indians. Tracks of American horses, mules and cattle were clearly indicated. Yesterday, in passing through a beautiful glade of timber, we found cut in the bark of a tree the name of J. Hardman, supposed to be one of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. The date of his passing on this trail was July 11th, 1833. Some of the comrades expressed much satisfaction on beholding the signs of white men who had preceded the command over this wild mountain trail more than thirty years before.

We emerged from the mouth of this wild gorge where the river turns abruptly north, while the expedition maintained its course in a westerly direction, through beautiful glade of timber and meadow valleys, in one of which was found ripe strawberries. Here, in this beautiful little glade, the Indians had taken advantage of their opportunity and had widely scattered their band of stolen horses, in order to confuse and throw their pursuers off the trail.

On entering this valley a halt was made, and while the horses hastily nipped a few bits of the luxurient grass the troopers dismounted and ate the strawberries. Too soon, the order came to mount and march and then after searching more than an hour, the trail was again discovered and the march was continued to the east bank of the great south fork of the Snake River, into which the trail of the Indians was found to enter. After some consideration by the commanding officer, the order was given for the volunteers to prepare to swim the river by removing their clothing and binding them to the saddle with their belts, and when thus prepared they began their struggle to cross the mountain torrent some two hundred yards in width.

In this, the expedition had much difficulty. The Indian trail led over a bar formed at the junction of three large streams now immensely swollen by the melting snow of the Tetons. Captain Smith led the way, the men following in single file, and after much difficulty he, with several other of the command, succeeded in landing on the west bank of the river. On looking back, those who had reached the shores safely saw that Donald McNichol's horse had become unmanageable, refusing to breast the current. He was swept down the stream several yards, McNichol apparently trying to guide him against the current, when suddenly it fell into a deep underflow and almost instantly disappeared. McNichol, however was seen to come to the surface and was swiftly carried with the current down the stream beyong all human aid. The Captain and Sergeant Spencer ran down the bank to his assistance, but the current was so rapid that he was carried quicker than their utmost speed, and very soon went out of sight. Comrade McNichol was one of the best swimmers in the company, but having his clothes, boots and six shooter on his person, he was unable to battle successfully with the watery element and his comrades saw him swept out of sight by the swift torrent.

On arriving at the west bank of the stream, the Adjutant called the roll and found no answer to the names of comrades McNichol, Lt. Knowlton, and Corporal Young, who were missing from the ranks. On inquiry, it was learned that the last two mentioned mission comrades had not been seen since the scattering of the force in search of the Indian Trail in Strawberry Valley, several hours earlier in the day. Captain Smith immediately called for volunteers to return on the trail in search of the missing men. Sergeant H.W. Spencer immediately responded and stated that he was willing to return along the trail in search of the missing comrades if Sergeant Riter would loan him the use of his horse on which to recross the river. The reason for this request was apparent in the fact that comrade Riter's mount was a very fine sorrell mare, one of the largest and best in the command and it was concluded that this animal would be able to face the rushing current of the stream with Sergeant Spencer on her back. Comrade Riter willingly accepted the proposition, and on this spendid animal, Spencer succeeded in breasting the swift current and, returning to the east bank of the stream, he retraced the steps of the company toward the little valley in the timber where the two lost comrades were last seen. After about four miles on the trail, he met them and gladly piloted them to the crossing of the river, the three following the same direction in crossing given by the Captain to those who preceded them. They succeeded in making the west bank safely, and were warmly greeted and welcomed by their comrades. Sergeant Spencer was cautioned on starting back on the trail not to mention the drowning of Donald McNichol until the arrival of the two on the west bank with the rest of the command.

The Indians at this point could not be far in advance of the expedition, but there were not six horses fit to travel another day, at the same rate of speed, and the command being entirely without rations, it was concluded that unless the Indian trail should take a direction in which the expedition might find means of subsistance, this pursuit would have to be abandoned.

On the 26th of July, at sunset, all but Donald McNichol had succeeded in crossing the Lewis Fork of the Snake River and, after a small ration, the boys retired for the night by spreading their blankets out in the open, for they had no tents, guards chosen and set, a quiet night ensued. At 5:00 am on the 27th, camp called, and on assembling, a proposition was made to the men to decide what would be best; to still pursue the Indians and take their stronghold and take chances in a rough and tumble fight with them, with men and horses fairly jaded with their long and furious chase, with firearms wet and rusty, or should we withdraw from the trail and follow the river in quest of game. The latter course promising the best results was concluded upon. Mr. Hereford, who was more interested in the recovery of his stolen horse than any other, expressed himself as satisfied with the efforts already made, and said that Captain Smith and his men had done all that men could be required to do. As we had neither rations or men or horses, he advised that we leave the Indian trail and seek for food, and the most direct way back to civilization. Accordingly, we took our course westward, and followed an old trail over the divide between Jackson Hole and the entrance to the Teton Basin.

Through the beautiful valley of the Teton, we went by slow marshes, allowing the horses frequent grazing opportunities and the men to rest, for strenuous travel was impossible as lack of food was already beginning to tell on the men. Early in the day a small cinnamon bear was roused from his den, some of the boys gave chase and succeeded in overtaking him in a dense grove of quaking aspen, where he was soon dispatched and divided among the men. A swan and badger also added to our catch during the day.

When we camped for the night, a few miles west of the lower end of Teton Basin the men were refreshed with wild game captured during the day and lay down to rest, more cheerful and comfortable from this partial satisfying of their hunger. Our mess of eight has for its portion the skin of the badger, which was placed on a bed of live coals, when the hair and fur were completely singed and burned away, then the bared skin of the beast began to sizzle and roast, and by this process of roasting, the thickness of the hide increased to at least three quarters of an inch. When thoroughly cooked through, it was divided among the eight men of the mess, and after devouring each his portion, with the rest of the party, we rolled on our blankets and slept for the night.

On the 10th day we resumed our travel, still in a westerly direction until we struck a branch of the Snake River. We hoped to be able to cross successfully this small stream, and then continue south and find the large river divided into smaller streams, thus enabling us to cross the tributaries, which would bring us to the south shore of the main Snake, where we hoped to continue our march through a country well supplied with wide game, accordingly a number of the command entered the stream, and swam with their horses to the other shore. Among the first to land was Corporal Young and Private Charles Crismon. While the first named trooper succeeded in landing safely on the other side, Crismon's horse seemd to have been taken with cramps, or else his feet became entangled with the stirrups of the lariat attached to the saddle, at any rate he soon became helpless and sank to the bottom. Comrade Crismon immediately disengaged himself from his horse, swam over, and joined comrade Young. Crismon not only lost his horse but his saddle, bridle, and all his clothing. On our return to camp the following evening, the comrades made of him a suit of clothes, and he was given one of the pack animals with the pack saddle to ride until a better mount could be found for him.

Arriving on the island, the two waited further developments. Some of the boys constructed a small, frail raft and, placing it in the stream near the shore, the three of them who could not swim, namely: Jimmie Sharp, Joe Fisher and Joe Goddard, embarked on the boat and on pushing off from the shore, they were instructed to lie flat on the raft and paddle and steer with their hands to the other side, which it was believed possible for them to do, since the current was quite slow and the stream not more than two-hundred feet wide, but the raft was too frail and immediately began to sink. Finally the boys had to stand on their knees, then on their feet, to keep their heads above water.

By the time Captain Smith, Jimmy Wells and others had crossed over and joined comrades on the raft, which was now drifting with the current in the middle of the river, the boys on it unable to guide or help propel it to either shore. Several of us ran hastily down the bank, following the course of the raft, till it drifted nearer the island, when Jimmie Wells, with the loop of a long lariat slipped over this right arm, plunged into the stream and swam with the current till he overtook the floating raft and shouted Pull.

In the meantime when Wells entered the stream other ropes were added to the one he had trailed behind him, so that he shouted to them on the shore to pull, the comrades on the trail raft were soon safely landed. After this very exciting experience several of the comrades explored further to the south limit of the island. There it was discovered that the big Snake River swollen as it was from the melted snows of the Teton Range, would present an obstacle probably insurmountable in the way of their progress in that direction. It was therefore concluded that the swimmers of the morning should recross to the mainland, one of them carrying a line attached to the raft across to the main shore. The same three comrades were placed again in the frail boat, but this time they were drawn speedily and safely to shore without delay or accident, landing near the same point from which they had embarked earlier in the day.

Here camp was established for the night and campfires plentifully provided that the men might stand around them and dry their wet clothing. Later in the afternoon comrade Joseph A. Fisher approached the commander and after saluting said Captain Smith, this is my twenty-first birthday, (June 28th) and I would like to have a birthday dinner.

The Captain replied, Well, we'll do the best we can for you Joe.

Accordinly a shank bone of the bear was fished out of the pack and placed in the camp kettle half full of water and hung over the fire. Comrade Hale brought out a flour sack that had once contained flour, turning it wrong side out, it was found that in mixing dough in the sack, some of it had adhered to the inside, this was scraped off and added to the kettle of soup. With the scrapings from the flour sack and some frog legs, added by comrade Hale, a kettle of broth without salt or seasoning of any kind was produced and comrade Fisher records that twenty men ate from his birthday kettle of this soup. The following day, July 29th, we marched fifteen miles to the south fork of the Snake River, secured some dry quaking aspen logs, constructed a raft and Captain Smith, O.H. Spencer, Andrew Bigler, S.B. Young, Peter Corney, James Sharp and Tom Caldwell, with the baggles of their mess, succeeded in crossing over.

On reaching the opposite bank, most of the boys succeeded in grasping the limbs of a cottonwood tree which had fallen over the edge of the stream. It was designed to pull the raft ashore and fix it with ropes for the ferrying over of the balance of the company, but the current was too strong so that the raft was swept from under them all, one of the comrades succeeded, however, in reaching the shore safely by the aid of the limbs of a tree to which he clung. Captain Smith, seeing Caldwell still on the raft and being carried swiftly down the river, plumged into the stream and swam until he over took the raft, climbed on it, and with comrade Caldwall continued down the swift current of the stream for more than a mile. It was near the main encampment where it lodged on the point of an island. Here William Longstroth swam with a long rope from the shore to the rescue of the two men on a raft, making fast the rope to the raft, the three were soon hauled safely to shore, with loss, however, of the two saddles some cooking utensils and some clothing.

The five comrades namely; Corney, Young, Sharp, Bigler and Spencer who had succeeded in landing upon the island when the raft got away found themselves being without clothes suffering intensely from the bites of mosquitoes that seemed to envelope them. Two the the comrades rebelled against this terrible mosquito scourge, and determinned to swim that night back to the opposite shore to obtain their clothing and be with their comrades in camp through the night. These two were Bigler and Corney, who made their way through brush and bramble several hundred yards up the stream where they secured a dry quaking aspen log and succeeded with it, in crossing again this mountain torrent.

The other three who remained on the island, Spencer, Young and Sharp, endured as best they could the bites of the hungry insects through the long weary night, naked as they were, with no defense against the onslaught of the millions of mosquitos. At daybreak, however, the three comrades followed the trail of those who had crossed the night before, going up the stream several hundred yards and there securing a dry log, and pushing it into the stream, and by its help were able to reach the shore from which they started on their perilous voyage the day previous. They were warmly greeted and welcomed by the Captain and comrades in their camp a mile farther down the river.

It was determined at this point that the command would make no further effort to recross the south fork of the Snake River as two attempts had already failed, in both instances nearly costing precious lives. After these escapades the following day, the 30th, we continued our march westward along the course of the river, but owing to the condition of the men, on whom the want of food was beginning to tell seriously, the company halted soon after noon and our wagon-master, comrade Sol Hale, was commissioned to interview Captain Smith and obtain from him permission to kill one of the horses and divide it among the men, this to relieve their hunger and husband what little strength remained.

Captain Smith consented, and requested comrade Hale to select one of the horses and shoot it and see that it was properly prepared and delivered to the different messes according to their number. The horse was selected, tethered to a sage brush, and comrade Hale walked to within ten or twelve paces of the animal, leveled his six shooter and took deadly aim at the doomed animal. We all stood expecting to hear the report of a gun, and to see the poor old faithful beast drop dead, but Hale did not fire. All of a sudden he dropped his hand which held the gun by his side and said, tears blinding his eyes, Darned if I can shoot that poor old horse.

Then another trooper, Jimmie Larkins, was selected to do the killing. The horse was soon divided and each man began to roast and eat his portion while the cooks engaged in boiling the larger and more boney portions for a more substantial meal. It was observed that Captain Smith was not eating. A comrade secured a piece of seemingly healthful liver and after roasting it over the fire, the Captain was induced to eat a portion of it. The comrade also made his supper of the roasted liver not being able to eat the boiled meat, prepared as it was without salt or seasoning of any kind. The fresh smell, coupled with the stronger odor of the horse, was sufficient to prevent any desire for the horse flesh that night, but the following day hunger overcame every other consideration and a hearty meal was made of the boiled horse flesh.

July 31st, we reached the north fork of the Snake, at a point near the two buttes, about seven miles west of where Rexburg is now located. Here, the remnants of the slaughtered horse was devoured and the boys worked vigorously hauling, with their saddle horses, dry logs from a little clump of trees several miles away with which to construct a raft. The following morning, the first day of August, Mr. Hereford superintended the construction of a substantial raft, binding the timbers firmly together with thongs of raw hide, cut from the side of the slaughtered horse, and with this raft the men who could not swim and the baggage of the company was safely ferried to the other side of the stream. Though very deep at this point and at least thirty rods wide, the current being sludgy, enabled the remainder of the men to swim over with their horses without difficulty. They then crossed over a very swampy piece of ground which was bridged with willows. The men carried the baggage and their saddles across this willow bridge, because the horses had all they could do to walllow through the mire without anything to carry. Soon after crossing this swamp, a small branch of the river was encountered and successfully crossed and the company safely landed on high ground near the foot of the two Buttes mentioned.

On August 2nd, the company marched twelve miles, and halted to allow the animals to graze and rest at this point. Captain Smith and Corporal Young rode in advance for the purpose of finding and intercepting any company of emigrants that might be traveling to the north. After riding some fifteen miles, a small group of about eight wagons was overtaken on the road leading toward some newly discovered mines in the northern part of Idaho. They were camped for their mid-meal.

After much solicitation, they reluctantly furnished us a hundred pounds of flour and a side of bacon, charging a very high price. The men stated that a few days before, Indians had attacked their camp and killed one of their men and ran off one of their horses and five of their cattle. Captain Smith gave up his horse to Corporal Young, the Corporal using his mount and saddle on which to pack the flour and bacon. When the pack was made up and thoroughly lashed, Young mounted the Captain's horse in obedience to the Captain's orders, and drove the pack animal swiftly on the way to meet the approaching column of famished men. Captain Smith was left to the tender mercies of the emigrants who had threatened, when we first entered their camp, that they would hang each one of us to a wagon tongue. We explained to them that we were members of a command of the Utah Volunteers of the United States Army, and also the fact that about forty men, belonging to the said, were a few miles in the rear and very in need of something to eat and, should harm come to us, vengeance might be taken upon those who did the injury. After this their venom seemed all to have passed away, and the provisions were furnished as above stated. The Captain marched along near the train, both coming up with with camp of volunteers about dark in the evening, at which time we had established our camp and was engaged in making bread and frying bacon to satisfy the hungry men. When the emigrant train had gone into camp near the volunteers, they seemed desirous of showing in every way possible, their regrets for the threats to hang Captain Smith and his comrade. They furnished two large kettles, with soup bones and plenty of fresh beef, also salt and pepper for seasonings. From these ingredients two brimming kettles of soup, with dumplings, were being ladled out to the men and the feast of this delicious supply lasted till midnight. From this time on till our arrival home there was not want of food. The following day the command marched twelve miles to the outlet of the Snake River which supplies Market Lake. Here we encamped and rested till the followinig morning at day break when we mounted our horses and swam the outlet of the lake, and with ropes attached to the pack animals, assisted them to cross the stream, by dragging them through it, part of the time under water with their packs. From this crossing we made our way twenty-two miles in a southwesterly directions when we reached the point of the Snake River called Eagle Rock, (Idaho Falls) where a ferry had been established by Barnard Brothers, from Box Elder Utah. After crossing on the Barnard Ferry boat, Captain Smith purchased of the ferry man, several sacks of flour and a dressed beef. At this point we obtained from Mr. Barnard a couple of wagons and some harness and hitching our pack by slow and easy stages, we traveled by way of Fort Hall and past the trapper's lodge where Pocatello is now located, continuing up the Fortneuf River, we marched to the present sight of McCammon and reached Soda Springs the second night from the ferry.

The following day we resumed our march down the Bear River as far as the north end of Cache Valley, and on reaching the little hamlet of Clifton, entered the defile of this mountain stream and followed it over the divide into Malad Valley. The next day we continued our march thirty five miles to the Bear River bridge, owned by Ben Hampton, over which we crossed without difficulty, by paying the stipulated price for man, horses and wagons. The next day we reached Brigham City, and the following evening camped a few miles north of Ogden, and in the afternoon, August 15th, about 4 o'clock we rode into Salt Lake City where we were warmly welcomed by President Young, General Wells and the populace.

Indians

Indians steal cattle near Ephraim, Utah. Captain Bigler with sixty men from Davis County arrived in Mount Pleasant,m July 12th, 1866 to relieve the Salt Lake troops. On Friday, July 27th, Indians made a raid on the stock of Ephraim and Manti and drove away one hundred and fifty head, Captain Bigler pursued them into Castle Valley without recovering the stock, or having an engagement.