Indian-White Relations

An interview with Mrs. Charles W. Hill; Reminiscences relating to her father-in-law, George W. Hill and the missions to the Indians in early Utah and Idaho history.

Mrs. Hill was interviewed at her home in Salt Lake City, 270 Reed Avenue, near Warm Springs, and on the very tract of land where the Indians were once used to visiting her father-in-law when he was in charge of Indians affairs. Mrs. (Frances Steele) Hill was 82 years old but in evident good health and spirits, mentally alert of sound mind and good memory. Present were Dr. C.E. Dibble, anthropologist of the University of Utah and Fred G. Barker, shorthand reporter, also of the psychology department of the University of Utah. The date was July 30th, 1945, about 10:30 a.m.

Dibble: Will you tell me something about yourself before you start talking about George W. Hill. Where were you born?

Hill: InWellsville, Cache County, Utah.

Dibble: And you spent your early years there?

Hill: Well, I did not live there so long; my father got shot when I was two months old, and my mother married again and moved to Mendon. My father's name was John Hill, and he came in 1850. He had helped to build the Nauvoo temple. I have a plane and a saw that he used on the Nauvoo temple. My father and his brother had a grist mill between Wellsville and Mendon, and the bears used to come down there and destroy their crops. So my father and one of his nephews were hunting for a bear, and there was a crowd of men came from Hyrum to hunt the bears too, and they heard the rattle in the bush and thought it was a bear, and they shot and killed father. Several bullets went in him, and he raised up and said, Boys, you have riddled me,

and died. My mother afterwards married a man named Amenzo White Baker, and moved to Mendon; and I lived in Mendon Until I was about fourteen. Then I came down to the (Salt Lake) city. Mother had eight children by Amenzo Baker, and four by father. My oldest sister was born, then my mother had a pair of twins, and then I was born, and there was not three years between us– my oldest sister was born in 1860 and I in 1863. My mother had four babies when father got killed.

Dibble: You speak of Mendon. As I recall, the Indians lived at Mendon at one time.

Hill: There used to be Indians there. I remember when I was a girl I used to be afraid of them. They were kind of mean. They thought that the people were driving them out of their country –they thought it was their country– and you could not blame the Indians hardly. And the same when grandpa (George W. Hill) came here in 1847, you know the Indians were pretty bad then. He used to have to guard (against) the Indians quite a bit. He was a big, strong, healthy man and used to be out on guard a good deal. And he got to liking the Indians, and talked to them. He had learned several languages. But you wanted my history first, didn't you?

Dibble: It all ties in, it all comes together. There was an old Indian here at Washakie, (in northern Box Elder County) that was telling me about Indians stealing a white girl there at Mendon. Have you ever heard that story?

Hill: Oh yes, I remember about that.

Dibble: How did it happen?

Hill: I do not know. They stole her and the people never did find her. They were very much put out about it, but they did not know what the Indians did with her. That was while I was a girl.

Dibble: Perhaps that was what made you afraid of the Indians, partly?

Hill: Yes, when I saw any of the Indians I used to run for home. I did not want to be out. I was afraid of them.

Dibble: What did Mendon consist of at that time?

Hill: Well, it was only a little town, a farming town, and there were farms all around. It is pretty close to Logan– it is up against the hill more from Logan. Of course, Wellsville, then Mendon. I can remember when the first train came into Mendon. We thought it was a big one then, but it was a narrow gauge.

Dibble: Did George W. Hill come in with the original pioneers?

Hill: George W. Hill was a pioneer, and came in 1847

Dibble: Was he very old?

Hill: He was a young man when he came. On the slip of paper I handed you it tells about his coming here. I was reading it this morning. There is a kind of a history that was put in the paper when he died. It tells about him shooting a bear that was interfering with them when he was coming across. He came here in 1847 and then went back and converted his father and brothers to the Gospel, and he brought his wife's family along with him. He went back and got them and brought them here after he came here himself and his wife came. Their oldest son was born on the plains. They stopped the wagon long enough for the baby to be born.

Dibble: His first mission to the Indians was in 1855, wasn't it? He went to the Salmon River country. I think he was interpreter for a large group that went to the Shoshone Indians.

Hill: Yes, when they first came here in 1847 the Indians were bad, and he used to be a watchman around to protect the Saints that came here, and then they built a big wall around here, the wall was right along there, just back of my barn, right north of my lot. It was a big high mud wall.

Dibble: Do you recall hearing Brother Hill speak of the baptism at Horseshoe Bend, when so many Indians were baptized? That was in 1875, I think.

Hill: I do not remember what year it was but I remember he told me there was a band of Indians that had been inspired of the Lord, I guess, and wanted some missionaries to come; so grandpa was one of the missionaries that went to this band of Indians, and I think he told me he baptized 500 Indians at that time. I do not remember whether it was at Salmon, or just where it was.

Dibble: The story is told of the time in 1875 when he was baptizing on the Bear River at a place called Elwood; and soldiers from Fort Douglas appeared and told the Indians to go home, and Brother Hill defended the Indians and argued that they had a right to be there. Did he ever tell stories about the testimonies of the Indians– how they came to have testimony of the gospel?

Hill: This one time when so many wanted him, they seemed to be impressed; they must have been inspired by the Lord. The reason they wanted missionaries to teach them the gospel. And Grandpa (George W. Hill) went with a crowd of the authorities, and he did not know the language of this band of Indians, but the Lord gave it to him and he was able to talk to them and interpret what they said to the brethren that were with him, and that language never left him. It always remained with him.

Of course he had gone on missions among the Indians a lot, before he came to the city (Salt Lake City) to take charge of the Indians affairs, and of course he got acquainted with the Indians and liked them, and he took lots of interest in them. He was honest with them, and they could depend upon what he said. The people who came here before our people came, were not very good to the Indians, but our people tried to ge good to them. And of course grandpa was a very good missionary among the Indians. Grandma said he was off a good share of the time among the Indians, working at different places –I do not know just where– but she said she was left alone with the children because he was off so much. When Dimick Huntington died, they brought him (George W. Hill) down here to take charge of the affairs of the Indians, and there used to be a big band of Indians come, and he would take them to the office where the President was, to let the President talk to them, and to interpret what the Indians wanted to know.

After he came here to take charge of Indians affairs, he did not go off on missions among the Indians; it was before that he used to go off on these missions to the Indians, but after he came here he did not go, because they kept him busy here with the Indians. Then there came a time when the Government was raiding the Latter-day Saints for plural marriage, and they could not do much with the Indians. He was busy then taking care of the authorities of the church and getting them out of the way of the deputies. He went past a crowd that was going to arrest President Woodruff, and he had a one-seated rig and a horse, and he had President Woodruff in the back of that buggy covered up with a robe of some kind. He went right past the deputies, and the deputies were going to arrest the president. He got them away a lot. I know more about that than about the Indians, because he used to come home and tell us. He went up to the office to do anything that the President wanted him to do. He got the authorities out of the way of the deputies a good many times and saved them from being arrested.

Dibble: You were telling me the other day about the testimony he had when he was about to die, that the Indians–

Hill: Yes, he dreamed that the Indians came to him and wanted him to go with them, and it was Indians that he knew, and he knew that were dead. He said, I cannot go now; I want to get my affairs fixed up before I can go.

They said, Oh, your affairs will be all right. We have got to have you. We have a lot of work for you to do, and we must have you.

And it was not long after that until he went up to the Tithing Office to see about his work, and he came home with an awful cough, and I remember I was here, and grandma got up to put a poultice on him; he coughed so hard that it scared her when she heard the cough, because she remembered this dream. He must have taken the La Grippe. We all took it, and we were not any of us able to be up or around, and we sent for help. His turned to pneumonia and he died. We all took the La Grippe from him.

Dibble: He was buried in Salt Lake City?

Hill: Yes, in the (Salt Lake City) cemetery.

Dibble: There were many Indians at his funeral?

Hill: I could not go to the funeral. I do not know who was there, because I was sick in bed with the flu when he was buried.

Dibble: He lived in Ogden, Utah for some time, didn't he?

Hill: Yes, for quite a while, until the President of the Church asked him to come down here and take charge of the affairs of the Indians, and he lived here ever since. I did not know Grandpa Hill until he came down here.

Dibble: He lived in Ogden at the time he was working with the Indians?

Hill: Yes, he was on missions a good deal when he lived in Ogden, but after he came to Salt Lake City he did not go out on missions to the Indians, because the Indians came here, and it kept hm busy here. There would be big bands of them come, you know, and he would take them up to the President and interpret what they wanted the President to know. It is funny that they have not said more about Grandpa Hill when he worked among the Indians so much. I have often wondered why there was not more published about him.

Dibble: His grandson tells me that very often his house was filled with Indians.

Hill: Yes, there were so many they could not all get in the house. There would be big herds come, and he rented a place when they asked him to come down here. It was in the 19th Ward– a way down that way. And this was just an orchard around here, and the church owned it, and they built this house for Grandpa Hill, and a house across back there (northwest) for the Indians. (She showed us the house, which has since been stuccoed, while the Hill home is adobe.) Grandpa had from this street, Second West, up to Center Street, the next street. He owned this whole place here before he died. The Church built this house for him, and the place for the Indians, but before he died he bought the whole strip from the Church, because he felt that he wanted to buy the place.

But he was not doing much with the Indians just then before he died, because it kept him busy with the authorities of the Church, trying to keep them out of the deputies hands. He was driving around to protect them, and he protected a lot of people here in this home. Three of his boys had more than one woman, and they were here, and I was one of them. And he took other people in to help them out. He was a very good man and did all he could for the people. He was not a polygamist himself, but had three sons that were. Grandma had gotten up in years and was not able to handle the Indians. They expected her to cook meat, and she used to have to put a boiler on. After the Church built that other house they put an Indian woman there to cook for the Indians when they would come in bands like that. Grandpa had a commanding way about him. They thought they had to obey him. The deputies thought he had more than one woman. They said, You can tackle him,

but none of them wanted to, and they never molested him. He had white hair.

Dibble: I thought he had red hair.

Hill: His hair turned white all at once, one when he was off working among the Indians. I do not know what made it turn white, but grandma said it turned white all at once and was as white as could be. Whether he got scared, or what caused it, she did not know. I saw his hair up in the loft; it was quite a bright red, and the Indians called him "Engumbambi," that was his red hair, I guess. They thought a lot of him, and he thought a lot of them, and he did all he could for their benefit.

Dibble: Was there an interpreter before George W. Hill?

Hill: Dimick Huntington was the only one I know of outside of Grandpa. Of course there were other men that worked among the Indians and could interpret, I guess, but I do not know that they had any here in Salt Lake except Dimick Huntington and Grandpa that I know. Those two were the only ones that I heard them say anything about. I do not know who they have had since Grandpa died or the the Indians stopped coming in. But Grandpa died when the Government was raiding the people so much it seemed as though they were not doing much with the Indians.

Dibble: That is, when the polygamy prosecutions began, that is when the Government began to persecute them for polygamy, the Indians did not–

Hill: The Indians did not come so much after that. I do not know why. Well, they did come some for a while, but not as much as they did before that.

Dibble: Possibly because they could not contact the authorities of the Church?

Hill: Yes, that might have been the reason; they might not have been able to get the authorities, they were on the underground. President Taylor died on the underground. I remember when he went on the underground. He went on the underground when I did. I had one child, and John Henry Smith lived just across the street from us in the 17th Ward, and he said to my husband, Hill, watch out; the deputies are after you or me, I don't know which.

So I had to go away from home for a while.

Dibble: The President of the Church died in Kaysville (Utah) on the underground.

Hill: I remember when he died. I was with his daughter, and she was feeling so bad when he died.

Dibble: Was that over a very long period of years, that underground?

Hill: It was for quite a while. I got married in 1882, and they were on the underground then. President Joseph F. Smith married us one evening at the Endowment House. We had to go there secretly, you see.

Dibble: I recall my uncle telling about the underground. That was B.H. Roberts.

Hill: Yes, he had several women.

Dibble: His one wife was a Dibble, Celia Dibble. That was, I guess, about your time.

Hill: I guess it was. You see, they married them until the Manifesto, and then they quit. The Government took the property, the temples and everything. So the Lord decided they could not practice that principle. Of course He gave it to them, but they could not practice it and do the work they should do. So he caused the Manifesto– it was really a revelation, I have always thought, that President Woodruff had, so that they could get the use of their temple and grounds there. So, of course that was why polygamy was stopped, on account of the persecutions. It is a good principle; it is right; I have always believed in it, and I do now, but of course I know it cannot be practiced now. It was a true principle. The Lord gave it to them. But when the people cannot do what the Lord tells them to do, and the Government interferes, of course they are not responsible; they cannot help it.

Dibble: Did the Indians who wee converted to the Church sometimes speak in conferences?

Hill: Yes, they used to come to conference quite a bit.

Dibble: They were also admitted to the temple, were they not?

Hill: Yes, I know some of them have been to the temple. They are a choice people, and when they are converted– I think that any class of people who are converted and know the Gospel are admitted to the temple, except the niggers are barred and cannot go. I think any other nation can, if they are true Latter-day Saints and faithful.

Dibble: Brother Hill thought of them as Lamanites, didn't he?

Hill: Yes, they were the Lamanites. You see, the Nephites– some of them were probable descendants of the Nephites, because they got mixed up, but of course the Nephite nation got killed. That is what the Book of Mormon tells us, that they got killed, and that the Lamanites were the only ones left; but naturally there was Nephite blood mixed with them. It seems strange how they would forget the Lord. But when they got rich, it seemed that they could not stay with the faith. A good many other people cannot, I guess.

Dibble: Well, it seems that Brother Hill spent his life doing two things: working with the Indians, and protecting the authorities. That was his life?

Hill: Yes, that seemed to be his life, and he took great pleasure in protecting people. I thought an awful lot of him. He was a very good man and raised a good family.

Dibble: He spoke a number of Indian languages, didn't he?

Hill: Yes, he spoke a number of different languages. There were different tribes of people came with different languages, and it seemed he knew quite a number of different languages and used to talk to them. But this one language came to him without study. He did study different languages when he was in Ogden.

Dibble: You do not recall which languages that was?

Hill: I do not remember. I guess I did hear about it, but I have forgotten.

Dibble: It says here that he spoke the Shoshone language, the Bannock, Flat Head and Nez Perce– that they are the four languages he spoke.

Hill: Well, I do not know which languages it was that came to him that he did not study. He never forgot it, but could always remember it, and talked to the Indians and interpreted what they said.

Dibble: Did the Indians ever protect him– or was he ever in danger so that the Indians would need to protect him in his travels?

Hill: I do not know, though I know they would protect him if he was ever in danger around where they were, because they thought so much of him. But I do not remember his saying anything about them protecting him.

Dibble: He did not keep a journal, did he?

Hill: Well, I guess he did. I think some of his boys must have got it. His son John was writing his history when he died. I do not know how far he got before he died.

Dibble: That is George R. Hill's father?

Hill: No, this was John Hill, his second son. He was a school teacher and lived in Franklin (Idaho) when he died, but she is living with one of her daughters, close to Mendon.

Dibble: I am going to Mendon tomorrow. Maybe I can inquire.

Hill: She might know something about it. She is older than I am. Her name was Martha Stowell, and then she married John, and that is Martha Stowell Hill. She lives with her daughter, on a chicken farm, I believe. Her granddaughter married a man by the name of Wille. You might be able to get some of that history. You could get a lot of information if you could get that history. I know John was here and told me he was writing a history, and I told him I would like to get it when he got it written. But he died without getting it finished, I guess.

Dibble: George W. Hill had three sons, then?

Hill: George R. Hill was his oldest son, John Hill was the second son and Charles W. Hill the third.

Dibble: Your husband?

Hill: Yes, and Parley P. Hill was the fourth. He had four sons, and they are all dead. There is me and Martha (John's wife), and Parley's wife is still alive. The rest are all gone.

Dibble: But you were more closely associated with him that the others, were you not?

Hill: Yes, because I lived here quite a bit. Of course my sister was one, we are all kind of mixed up. Mother had three girls, and John married one of them, my oldest sister. And Charles W. Married Jennette and me, the two younger sisters. So we all married in the family, the three of us, of father's children. Of course I was the youngest when father died.

Dibble: He must have been a wonderful man.

Hill: He was a wonderful man. Yes, I used to think there were not many men better than him. The way he used to take care of the Indians, and the way he used to house people in this house. They came here for protection, and he used to protect them. He did all he could. He said, I have not lived that principle, but I have taken care of a lot of them, and I ought to have some reward.

Following the foregoing interview, Mrs. Hill pointed out the little house built for the Indians, and said, It was adobe, but they have plastered it over. When we moved here in 1904 it was kind of dilapidated. It had been rented, and my husband cleaned it up before he died, and his mother came here and stayed until she died. She died in April, and my husband died in the fall of the same year.

The clipping containing the story of George W. Hill's life must have been from about February 26th, 1891's Deseret News. February 26th was the date he died.

Grandpa always took the Deseret News, and I have taken it ever sine I came. We moved back here in– after Grandpa died, my husband's first wife died about the same time, and then he took me down to Sugar House Ward, where he was living then, and we lived there about ten years, and then we moved to Pocatello for a couple of years, and then we moved to Rigby, and then we moved back here in 1904. And then he went down to see his mother, and she wanted to come up here, and he brought her up here and she staid here. I took care of her. She had a stroke and was helpless. I took care of her until she died.

Dibble: You probably lived among the same Indians then that Brother Hill preached to, if you moved north to Pocatello and Rigby. You lived near some of the same Indians that he preached to?

Hill: Yes, there were Indians there. My husband had a store there in Pocatello, and they called him Engumbambi's Papoose. They though a lot of him, and used to like to go and talk to him. Yes, there were lots of Indians used to come to his store in Pocatello and talk to him. He went in business in Pocatello but he did not seem to do very well. He went in with a man not honest, I guess, and then went to Rigby, (Idaho) and his health failed him; he failed in business then and we moved back here. He died in 1908. We were here four years before he died, but he was sick. His health broke down and he was not able to work.

Well, if I can answer your questions I am perfectly willing to. I am quite a reader. I had to work so hard though, after my husband's death, to raise the children, and did not get so much time to read. I worked myself down until I was not able to work. I had a heart attack, and was pretty bad for a while. I have been reading; I have read the Bible through once and half again, and the Book of Mormon. I knew all the authorities of the Church except the Prophet Joseph (Smith). Brigham Young used to come up to Mendon. I was not so well acquainted with them, but when he he used to go to Logan conference, he would pass through Mendon, and we children would all go down to meet the train, and he would come out on the platform and talk to us Sunday school children. So I have seen him and heard him talk, and then, of course, the rest of them I have been pretty well acquainted with.

Dibble: Whenever Brigham Young went to the Indians he would take George W. Hill with him, wouldn't he?

Hill: Well, I think that Dimick Huntington was interpreter then, in Brigham Young's day. I think it was in John Taylor's day that George W. Hill came down to take charge of the Indian affairs. He did not do that until Dimick Huntington died.

Dibble: The Indians seem to have received the Gospel very readily.

Hill: Sometimes they did very readily. It seemed as though they were anxious for it. Of course there were some who were not. He hd to talk more to some. But he was a good hand to talk to them. He had a scroll with pictures of the authorities and the Book of Mormon. It was a big scroll, about that square (eighteen inches), and he used to have that when he talked to the Indians, and turned to different characters and told them about their forefathers. I do not know what became of that scroll, but I know Grandpa had it. It had nice large pictures of the different Nephites and different leaders. The Book of Mormon tells about them. He had pictures taken on purpose for that, so that they would have something to look at. They were like children and he could explain it to them better. I have seen him have this scroll and talk to the Indians, and show them the different ones, who they were on these different pictures, and they were quite interested in it.

Dibble: Is it possible that they were the colored Book of Mormon pictures, by Ottinger and Hafen? The Ottinger pictures showed the Indians as almost black. The Hafen pictures gave them a lighter, browner skin. The charts of these pictures were issued by George Q. Cannon, for the Sunday schools.

Hill: I do not know where Grandpa got it, but the Indians could understand it better with the pictures.

Dibble: Of course the Indians would not read English; it would have to be explained by him.

Hill: Yes, he would have to explain.

Dibble: And were there any testimonies of healing when the Indians would get sick? Would the missionaries and Brother Hill administer to them? The sick children or the sick women?

Hill: Yes, I think he has related some of those, where they have been healed. It seems to me that he has told me that he had administered to them. They had lots of faith, when they believed in the gospel. I know this Indian they had here, had lots of faith, and when she did not feel good thought he ought to bless her. Grandpa Hill was a Patriarch, and gave patriarchal blessings.

Dibble: Do you recall whether he gave such blessings to some of the Indians.

Hill: I do not know. But I know he gave patriarchal blessings. He gave me one before I was married, and it seems like it has all come true. Yes, when I was a girl, before I was married, he gave me a patriarchal blessing. I do not know that I have seen him given Indians patriarchal blessings. I do not remember that. If he did, I do not know about it.

Dibble: I would like to see that picture of him again.

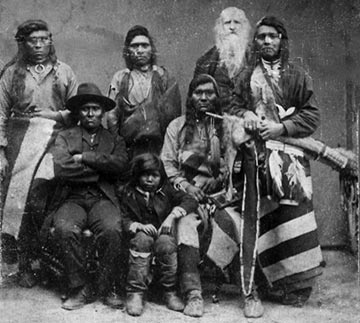

Hill: (Taking us to the next room) He had one large one taken, that the Indians wanted. He got that at (C.R.) Savage's, and then the children all wanted their mother to have one, and so we took her up and got hers done. This picture (on the wall) is the one he had taken for the Indians. (Shows a long white beard, over twelve inches long and rather full, the sides of the face contributing to its breadth.)

Dibble: That was taken when his hair was white.

Hill: He had white hair ever since I knew him. I saw his read hair' it was up in the loft once when I was cleaning, and I asked Grandma whose hair it was, and she said that was Grandpa's hair, that he had had it cut off once.

Dibble: I am looking toward publication, and I will want a picture if I publish the information I get.

Hill: (Paging the albums of old photographs) If I can find one of Grandpa, I will give it to you.

Dibble: I will see, too, if I can locate this article in the Deseret News.

Hill: I have a granddaughter who is is working in genealogy, Frances Baker, ever since she came home from her mission. My sister died and left five children, and I raised them with my own. I call them mine.

Dibble: It says here (in the clipping,) that Brother Hill married in 1845, Miss Cynthia Stewart. That means he was married before he came to Salt Lake?

Hill: Yes, they went to the Endowment House after they came here, but were married before they came here. They were not in Nauvoo. You see, Grandpa Hill was not, but my father was. He got his endowments in Nauvoo. He was married and had a family when he came here, and his wife died and my mother married him after his wife died. My father and all these children joined the Church about the same time as John Taylor did, in Canada. They moved from Scotland to Canada, and got the Gospel in Canada, and moved from Canada to Nauvoo.

Dibble: Thank you and I hope we have not troubled you too much.

Hill: That is all right.

Dibble: I think he was a great man.

Hill: He was a good man, but I believe as much as I believe anything that he was called on the other side, that he had a mission on the other side. You know, my sister was a twin, that married my husband, and she had a pair of twins. And she had a dream that she saw two lights,– one came and stayed for a time, and the other appeared and stayed a little longer, and it went. When she was sick with those twins, her twin brother was there all the time she was sick. He would come and look at here every paIn she had. He would come and then disappear. My mother and sister where there with her, but she did not tell them Archie was there, because she thought they would be afraid he was after her. She thought, though, that he was there for somebody, and the little boy died just a little after it was born, and the little girl died at about four and one-half months; so her dream came true. And then before she died, Archie was there to see her again. She was expecting to be sick again, and that was when she lived in Sugar House Ward. She did not feel safe.

That was when my husband was building a house down in Sugar House Ward. He built a big house. And it seemed that every place she went she was in danger and did not feel safe. But one night– we had two big rooms, and just curtains between the two rooms, and she was sitting by the fireplace a little while before she died. He came and looked at her, came and stood there between the curtains, pushed the curtains aside, and stood there and looked at her, and she knew he was there for her and thought she would die when her baby was born. She expected to, and thought he was after her. And he came and saw her several times before she got sick. And then she got sick and came through it all right. She told the people she would not live; she said she would die when the baby was born. But she did not get over it, really.

The doctors worked and worked with her, and she never was right. She said, I have got to die; leave me alone.

She begged Mother to make the doctors leave her alone. She said they were hurting her all the time and that she had to go. And finally she said, Archie is here waiting for me. I can see him. Let me go in peace. Do not make me stay here and suffer any longer.

They tried to hold her and did not want her to go, but she did go. She left the baby, and it was about four and one-half months old when it died. She left four more children, and I raised them. She was an extra-good women, a better woman than I am. Archie, her twin, had died when he was about sixteen years old, and when anything was going to happen, it seemed like he came, I guess because he was her twin brother and seemed closer. But she was a good woman. We always wanted to be together.

Note: A copy of the colored, lithographed Book of Mormon picture is in Andrew Jensen's historical museum at Salt Lake City. Albert Hooper, one time manager of the Sunday school Union Book Store, told me that the pictures were made with the Indians in mind, that a fire had destroyed the stone lithograph plates of the large eastern firm who made them, thus shutting off a very colorful appeal to the Indians and children. Mrs. Hill said the pictures George W. Hill used did not show the Indians as extremely dark. Hill's may have been earlier than even the Ottinger pictures. That would have to be checked up.1

- Interview with Mrs. Charles W. Hill, Charles E. Dibble, 30 July 1945. (Reminiscences relating to her father-in-law, George W. Hill and the missions to the Indians in early Utah and Idaho History.) ~Wikipedia Link to C.E. Dibble